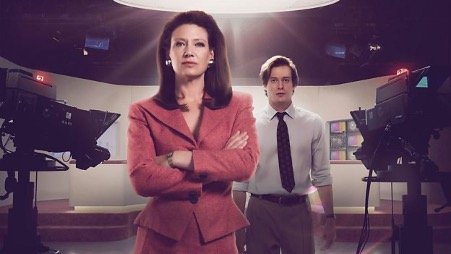

DBT ON TV - a close look at The Newsreader

This may be the only series that I’ve watched, notebook in hand. And that’s because, in season 3, brilliant, troubled, TV journalist Helen Norville unknowingly ends up with a DBT therapist! How fab is that? I almost fell off my sofa. I don’t think DBT has ever been given this much attention in a drama. It’s a fantastic advert for the therapy which is still so hard to access over here, but much more embedded, I’ve now discovered, in Australian psychiatry and psychotherapy.

To go back a bit… by the time Helen goes into therapy, there have been suicide attempts, days lost to drink and drugs, destructive relationships, spectacular, scary outbursts at colleagues and friends. And her past haunts her – hospitalised when she was sixteen, and diagnosed as schizophrenic. Helen won’t talk about it, and the gossip columnists regularly try to run scoops on it until lawyers intervene. She’s estranged from her family, didn’t go to her father’s funeral and she’s always in flight, from herself. Oh, and she has to keep charming her long-suffering doctor for Valium prescriptions.

Early in the series she tells her friend, and fellow broadcaster Dale, why she’d taken an overdose. -“All the nasty things people have ever said, going on and on in your head. You just want it to stop, some quiet.”

The Newsreader is set in the 1980’s and Helen’s workplace, News at Six is awash with sexism and racism. It’s a place where white men usually get the best jobs. Helen’s uneven mental health is often used against her. She’s described by her villainous boss Lindsay as a ‘warzone on two legs, a nightmare.’ She’s told that no one else will employ her, and that she’s not feminine (soft) enough.

But when Helen’s not in in a downward spiral, she’s resourceful, resilient, intuitive – “I always come good when it counts,” she tells the network’s boss.

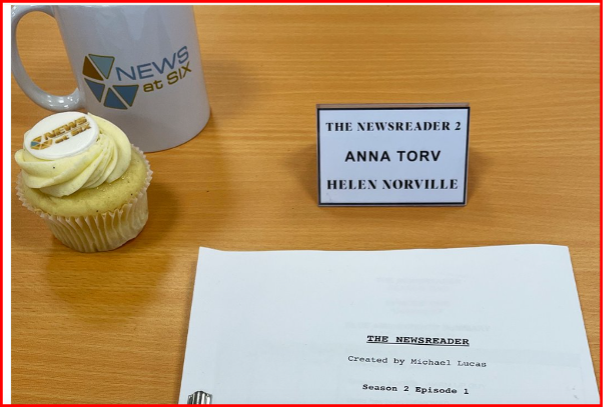

In the second series, Helen, running away from a problematic relationship, travels to Washington and the UK. She wins awards for her coverage of the Lockerbie disaster. When she returns to Australia, she’s given her own show -Public Eye - but hardly before the first episode has run, she’s had one of her explosive outbursts, in full view of the office. Her producer Bill insists she sees someone – a therapist who has helped a friend of his.

What follows is such a good dramatisation of DBT that it needs to be broken down, session by session. Training providers take note – your DBT resources just got a lot classier.

First session – Breathe!

Helen arrives for her first session and sits down on a large white sofa, which doesn’t look at all containing.

Helen: “I’m struggling.’’

Therapist: “How long have you been struggling?”

Helen: (crying) - “My life, my whole life.”

The therapist, who’s called Marcia Evans (note that the writers drew heavily on the life of DBT creator Martha Linehan for Helen’s story) is right in there with some strategies to help with Helen’s angry outbursts. She hasn’t yet told Helen what sort of therapist she is.

“How long have you been struggling?” “My whole life…”

— Michael Lucas (@MrMichaelLucas) February 9, 2025

Next ep, Helen finally moves towards diagnosis- after two seasons of Anna carefully playing a condition without naming it. I’m biased… but I think it’s some of Anna’s most extraordinary work. #TheNewsreader pic.twitter.com/8qFN8BZvIt

Therapist: “The next time you feel this reactive rage, I want you to stop, notice the room you’re in, notice your breath, notice your body and just observe.”

Helen: (Laughing) – “You’re telling me to shut the fuck up.”

Therapist: “I want you to consciously go through the stages before you respond. As an experiment.”

In subsequent scenes we see Helen trying out her new skills in work meetings, with some success. And then she takes a trip to an academic library with a very specific request - “to see journalism and periodicals on behaviour therapies in recent decades.”

Second Session: Can I ask you a question?

Helen and her therapist Marcia discuss how trying the new skills (to get her anger under control) have gone. Martia starts with a bit of praise –

Therapist: “You didn’t lash out, you stood your ground, you were fair.”

Helen then moves in with the new knowledge from her library visit.

Helen: “Can I ask you a question? These skills – are they related or connected to Dialectical Behaviour Therapy?”

Therapist: “You’re familiar with DBT?”

Helen: (With rising irritation) – “ Well, I’m a journalist, Martia, so I did a bit of research and I’m hoping you can enlighten me.”

Therapist: “Yes, it’s a new therapy. I think of it as a skillset for managing intense emotions.”

Helen: (even more irritated) – “It’s pretty heavily linked to Borderline Personality Disorder – am I correct?”

Therapist: “You’re familiar with Borderline Personality Disorder?”

Helen: “Well, it’s pretty dire. Manipulative, hysterical, promiscuous [behaviours]. Apparently there’s no fucking cure for it. So why am I here?”

Therapist: (Clears throat and pauses)- “Well, perhaps it would be worth us stepping through the actual criteria.”

Helen: “Please.”

Therapist: “It seems that you have quite a negative rhetoric around the disorder.”

Helen: “Is there a positive rhetoric around it?”

Therapist: “My colleagues at the University of Washington are seeing excellent results with this new therapy, and I myself have treated many patients with the exact symptoms that you’re exhibiting now.”

Helen: (Furious, and scared) – “Is that your diagnosis, Marcia?”

Therapist: (Utterly calm) – “Helen, we’ve been discussing your emotional reactivity from our very first conversation. And your fear of abandonment. And those are two of the main criteria. We’ve also covered the instability of your relationships. You’ve mentioned risk-taking and behaviour you describe as hedonistic. That already accounts for four of the nine criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder. So yes, Helen, in my professional opinion, a diagnosis is worth considering. But that is something that takes time.”

Helen: (Getting up to storm out ) - “Oh, you’re a fucking bitch.”

At this point it’s worth noting that while Linehan was indeed having success developing her new therapy in Washington in the late 80s, Martia wouldn’t have been helping anyone as DBT didn’t even reach Australia until at least the mid-90s. You can read a bit about its arrival here.

Back to Helen. She walks out of Marcia’s house, slamming the gate as she goes. And, like so many times before, she hits the booze and the Valium. Her producer Bill sends her home, and later, Dale, the friend who best understands her, comes over and finds her wrecked in the corner of her living room.

We discussed for months how Helen might respond to a BPD diagnosis. We researched, spoke to specialists, shared stories. And Anna, Sam and a very limited crew brought it all home in one staggering impro. What you see is the first take! #TheNewsreader pic.twitter.com/RwPAlELp7M

— Michael Lucas (@MrMichaelLucas) February 16, 2025

Helen: (Crying) “I’ve been seeing this therapist. She’s been really good. She’s given me all these kinds of ways to manage my emotions. But now she’s said that I am just fucked. It’s not like I’m sick - it’s just my personality, She says it’s a personality disorder. And it’s true. It’s just true. Do you see it?”

Dale: (Hugging her) – “Helen, all I see is you. I don’t think it makes a difference. Do you feel different?”

Helen: (Laughing) – “No, I don’t. I fucking don’t. Thank you.”

Hats off here to Dale (who has his own struggles) for his wise and compassionate response.

Return to the sessions: ‘I’d give Opposite Action a 3.’

Helen, now more at ease with her diagnosis, is back on the white sofa. Helen and Marcia discuss a key part of DBT treatment – the diary cards a patient uses to keep a record of their daily emotions, and the DBT skills they use to manage these emotions.

Therapist: “How did you go with the cards?’

Helen: “I found it really difficult.’

Therapist: “ I know filling out the cards can feel exhausting, but it’s really important you do fill them out because it helps us identify patterns within the chaos.’’

Helen: “I don’t have the time. The endless stream of banal, infantile, monotonous checklists.’’

Therapist; ‘(Energised) - “Alright, so we’ve got reactive anger right now. So which skill would you use?’’

Helen: (Exasperated) – “Jesus Christ! Thank you so much, Marcia, for your patience while I work through my issues with this particular style of therapy.’’

Therapist: “Helen, if there were a pill that treated Borderline, you would have it. But there isn’t. This therapy requires your full engagement. You know what the alternative is. It’s these cycles of reactive anger that erode your relationships. That you manage with booze and Valium. So, if you want that, no one’s forcing you to be here. You’re welcome to go.’

Helen: (Sobered by Marcia’s message) – “I’d give Opposite Action a 3 in terms of effectiveness. Breathing – I use that all the time, actually. It’s incredibly effective.’’

One of the unusual features of DBT is that the patient is allowed to contact the therapist by phone between sessions if they get into a crisis they’re struggling to resolve by themselves. DBT was originally designed to help a high-risk patient group who would be very likely to harm themselves whilst in distress. So the phone line offers a different route out of a crisis.

Helen has got into a difficult and painful situation with an Aboriginal activist called Lynus. Throughout the series, Helen is consistently shown seeking out Aboriginal perspectives, and arguing ( against a lot of opposition) for these stories to be broadcast. But she hits trouble with Lynus when she doesn’t immediately understand how racist policing fits into a story they’re working on.

“Oh Helen,’’ Lynus says, sighing. “Auntie was right about you. I thought you were one of the good ones.’’

This sends Helen into a tailspin. We find her hiding under her desk at work, and phoning Marcia, to ask what she should do next.

Therapist: (Firmly) – “You call on the Distress Tolerance Skills. Have you used ice?’’

Helen: (Shouting) – “I am in my office!’’

Therapist: ‘“Okay then, physical exertion! Is there a staircase?’’

Helen: (In great distress) – “I feel as if I’m meant to be feeling this.’’

Therapist: “Yes, this is an awful situation, and your feelings are valid. This therapy is not about denying your feelings. It is about bringing you to a frame of mind where you can better navigate the situation. And right now, you need a Distress Tolerance Skill. So pick one.’’

Helen puts down the phone, and runs out of her office and up the stairs.

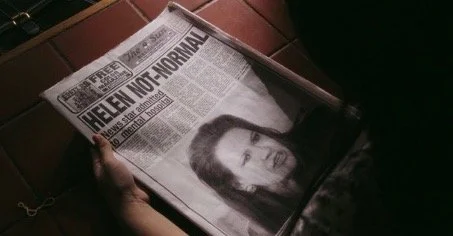

As previously mentioned, Helen ‘s past can always be used against her. News about her time in the Larundel psychiatric hospital (when she was sixteen) finally ends up in print.

Helen is distraught, and immediately phones her sister to ask her to publicly deny the story. Her sister gently refuses as “it’s all true.’’

At the same time, Public Eye proposes running a story on stigma around mental health, featuring a nurse employed at Larundel. Helen initially vetoes the idea as it’s far too close to home.

Helen goes to her therapist in crisis. Marcia reminds her that she’s a highly trusted newsreader, and then helps her to form a plan.

Therapist: ‘Helen, what can you always control?’

Helen: ‘My reaction?’

Therapist: ‘You control what you do next. And what you do next tells everyone who you are.’

Helen decides to work on the story. Her colleagues all now know about her past, and are on her side. In a team briefing, she says “We are going to have a ton of viewers tuning in to see a woman who was thrown into an asylum, and I would like for them to see a journalist.’’

When the show airs, and the nurse who worked at Larundel reveals that she too has been hospitalised for mental distress, Helen is free to reclaim her past. The show ends with a call for society to become more acceptant of mental health struggles.

Helen then says - “I would like to echo that. Having experienced anxiety and depression myself, I do believe that it is the shame and isolation that makes it so unbearable.’’

After the show airs, Helen’s sister gets in touch and they reconcile. Helen’s decision-making improves. She politely turns down an affair with her producer Bill , saying – ‘I couldn’t manage it, and you’re married.’

We see her new morning routine, - healthy eating, a spin on the exercise bike, and time spent with the dreaded, but essential, DBT Diary Cards.

Helen is now perfectly placed to deal with her next challenge. She wants to keep her show and appoint a female producer. She’s sat in a boardroom full of men. The network head shouts at her - “You do not get to control this. That’s the deal. Do you accept it?’’

Helen simply says no, and walks out. She gets her show – hurrah! -and her female producer.

Helen’s final, calm power move evolved over many drafts, and it was Anna’s idea to just have her say one word… “No”. Which, coupled with that magnificent Torv look, said everything. #TheNewsreader pic.twitter.com/azwVTV4dpc

— Michael Lucas (@MrMichaelLucas) March 9, 2025

If I knew how to access a DBT therapist like Marcia (all the best therapists are TV creations, sadly), I’d be there like a shot. Overall, The Newsreader is a superb series (it’s won lots of awards) and can be fully appreciated for its 80’s styling, great music and plot themes. The DBT strand is a bonus for anyone interested in the evolution of this therapy. And it’s such a relief to see Helen finally break free from her struggles, one diary card at a time.